Now then: you have a bet, possibly arrived at through some of the processes described in earlier modules of The Timeform Knowledge; you know what are its odds; you know what you think should be its odds; and you know how much money in total you have at your disposal. What should you do with that information?

In terms of general principles, it would be difficult to improve greatly upon the guidance issued in tongue-in-cheek manner by Timeform’s founder and lifelong atheist, Phil Bull, in his “Ten Commandments”, published in 1970:

“Let thy stake be related to the depth of thy pocket and to what thou regardest as the true chance of the horse; that which hath the greater chance deserveth the greater stake.”

Or, as it is more technically known, the Kelly Criterion.

The eponymous John Kelly was a remarkable character: a gun-toting Texan daredevil, physicist, early computer scientist and bona-fide genius who was reportedly inspired by corrupt wagering on the pre-recorded TV show “The $64,000-Dollar Question” to look into how a bettor, believing they have an edge, should stake optimally.

Optimally, in this context, meant the bettor never risked losing their entire bank. Kelly’s findings had a more immediate and intentional application at the time in what was the nascent field of information theory.

Anecdotally, Kelly initially presented his idea to his bosses at Bells Laboratories as a system for betting on hypothetically fixed horse races (this was the US: that sort of thing never happens in Britain, obviously) but was persuaded to make his content less controversial.

“A New Interpretation of Information Rate, by J. L. Kelly, Jr” came out in 1956 to very little acclaim – not least because the maths behind it is beyond most mere mortals – but gained popularity among a small number of investors and professional card players in the 1960s and 1970s and is now considered by many to be the final word on optimal staking, be it on the Stock Exchange or in betting markets. At least in theory.

The “at least in theory” bit is because there are a few real-world issues which mean that many bettors – including some who turn over vast sums on horseracing markets – use an adapted version of the Kelly Criterion rather than its purest form.

Fortunately, the abstruse maths have been simplified by some over the years, so that mere mortals can use a modified version of it also, including by Nick Mordin in his 2002 book “Winning Without Thinking”.

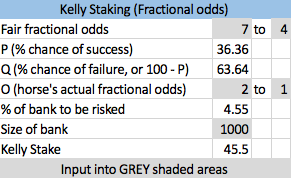

Mordin recommends the following: 1, Work out the chance, in % terms, that you think the horse has of winning; 2, Multiply this by the horse’s actual odds; 3, Subtract the probability, again in % terms, you believe the horse has of losing; and 4, Divide the result of the above by the horse’s actual odds.

The result is the % of your betting capital you should risk.

This can also be expressed as: (((P*O) – Q )/O) = % of bank risked, where P is the % chance of success, Q is the % chance of failure (equal to 100 minus P), and O is the horse’s actual fractional odds (or decimal odds minus one).

In an example in which you think a horse should be even money (50% chance of winning) and its odds are 2/1 (or 3.0 decimally), the equation gives you (((50*2) – 50)/2) = 25% of your bank.

An example of the Kelly Criterion spreadsheet is shown below, a download is available here so that readers can do such calculations quickly.

The real-world issues referred to a bit earlier include: that the bet you strike could affect the odds you secure (especially in pool betting); the unrealistic assumption that you will always get your bet accepted or matched to its full stake (or even at all); the difficulty in applying Kelly to coinciding and contingent events; and, perhaps most importantly, that – however good our judgement and/or algorithms – our assessment of probabilities may be flawed.

Anecdotally, some betting syndicates and big bettors use “Half-Kelly”, “Quarter-Kelly” or “Discounted Kelly”, whereby the suggested stake is factored down by an amount linked to the confidence in the assessment of the probabilities in the first place.

It is mathematically sub-optimal but seemingly a sensible ploy in reality.

Nonetheless, the basic principle of the Kelly Criterion – that you should stake according to the edge you have and the likelihood of the event occurring – is sound and should inform a sensible bettor’s approach, even if that bettor does not use the Kelly Criterion itself.

Discipline is highly important in staking as well as in selecting the bets you bet upon, with a rigid adoption of a version of the Kelly Criterion perhaps being the most disciplined approach to staking imaginable.

As with many other things, you either have discipline or you don’t, but it is possible to acquire it if you put your mind to it (and it is definitely possible to lose it if you don’t).

Remember, whatever else you do, to avoid staking which varies alarmingly for no good reason, and always be aware that no staking “system” ever devised can make up for fundamental deficiencies in selecting your bets.

0.png)

.jpg)

Url copied to clipboard.

Url copied to clipboard.

.jpg&w=300)

.jpg&w=300)

.jpg&w=300)

.jpg&w=300)