As the previous module in The Timeform Knowledge stressed, analysis of overall times can provide both very useful and all-but-useless information. That is because an overall time is subject to the pace at which a horse runs its race, and only truly-run or efficient performances will result in overall times which closely reflect the ability of the horse concerned.

All is not lost, however, for establishing the degree to which a performance was efficient is usually possible by taking sectional times along the way. What’s more, with a bit more effort, it is often feasible to adjust an overall time to reflect how that overall time was achieved.

Sectional times break the race into two or more “sections”, providing an alternative to a one-dimensional interpretation of the race from a time point of view.

Experience and historical data have shown that the most informative sectional juncture on the Flat generally occurs around 25% to 33% from the finish of a race.

So, in races at up to and including a mile, a final-two-furlong sectional might be “best”, while at nine to 14 furlongs a final-three-furlong sectional might be more appropriate, though the positioning of cameras is likely to dictate matters.

It is a relatively straightforward procedure to establish the sectional and overall times of individual horses from information available in the race result and that which is captured at the sectional. This, and much more besides about sectional analysis, is described at length in the free-to-download “Sectional Timing: An Introduction by Timeform”.

It follows that if you know a horse’s overall time and its closing sectional, the time before that sectional is implied, for it is the overall time less that sectional time.

The resulting information establishes a ratio between the speed before the sectional and after it. Because it is a ratio, you are comparing a horse with itself; and, because you are comparing a horse with itself, such a ratio has a universal application across all horses.

It is not necessary to use mathematics to get plenty out of sectionals, but there is one short equation which helps to put the available information into a much clearer context, and it is this:

A horse’s finishing speed % is given by: (100*sectional distance*overall time)/(sectional time*overall distance), with “*” indicating “multiply by”, “/” indicating “divide by”, and brackets indicating calculations which need to be completed before being reintroduced into the equation.

As an example, Gleneagles’ last three furlongs in this year’s 2000 Guineas was manually recorded at 36.16s, while his overall time for the eight furlongs was 97.55s.

(100*3*97.55)/(36.16*8) = 101.2%

The figures for the sixth-placed horse in the 2000 Guineas, Home of The Brave, were 37.81s and 98.74s.

(100*3*98.74)/(37.81*8) = 97.9%

This tells you that Gleneagles was finishing slightly faster than his average race speed, while Home of The Brave was finishing slower than his average race speed. It is then necessary to compare this with a “par finishing speed %” for the course, distance and circumstances involved: again, this process is described in “Sectional Timing: An Introduction by Timeform”.

Most sectional pars are close to 100% (or slightly over it, reflecting the fact that the overall time will include acceleration from a standing start whereas the closing sectional does not), but it depends on topography.

For instance, the par for the Derby distance at Epsom is around 111% on account of a particularly severe opening half-mile and a notably easy closing half-mile. By contrast, the par for the last-two furlongs of the Eclipse distance at Sandown is around 94% on account of the uphill finish there.

The difference between actual finishing speed % and par finishing speed % is what really matters. While it may be possible to judge pace in general terms visually, it is not possible to do so infallibly or in a way which produces hard figures like the above which can then be used to tell you much more.

Precise timing does that. Unfortunately, in the absence of precise timing funded by British racing, enthusiasts are obliged to take their own times or to subscribe to Timeform’s Sectional Archive.

Enough of the theory. How do sectional times work in practice?

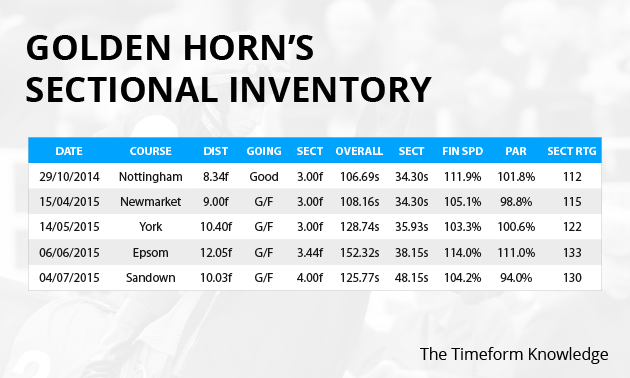

Let’s take this year’s champion three-year-old, Golden Horn, as a case study.

Golden Horn’s debut at Nottingham was an astonishing performance in terms of sectionals, which show he quickened like a Group performer to come from last in a steadily-run maiden. Those who chose to ignore sectionals rated it an ordinary maiden win, and some still maintain – in the face of the evidence – that the race was strongly-run and assisted Golden Horn in that respect.

His victory in a listed race at Newmarket on his reappearance was almost underwhelming in comparison, and especially in view of what he has done subsequently. But sectionals again show that he put in a strong finishing burst in a race not run to suit (again, some maintain otherwise to this day).

He then showed that he could record a classic-standard overall time in the Dante Stakes at York, but even then he finished more quickly than par (it was not a case of his benefiting from a “pace collapse” as some stated) which augured well for his staying further.

His Derby win at Epsom came in the best relative time of the year so far. Golden Horn had to be both very good and a sound stayer to beat the Dante runner-up Jack Hobbs again, and that is exactly what he showed he was. Even then, that finishing speed %, in a race in which many of the also-rans flagged, was faster than par and suggested there could be more to come from him.

Faced with a very different proposition in the Eclipse at Sandown – two furlongs shorter, and a steadily-run race as the sectionals confirm – Golden Horn underlined his versatility as well as his class by coming home a good deal quicker than par for another emphatic success.

Golden Horn is a favourable example of a horse identified as a classic contender at the outset, then as a likely classic winner, then as a classic winner in fact – while some remained ignorant of his achievements – of course. There are many instances which do not work out so well! But he is by no means unique in making the case for incorporating sectional times into analysis.

The likelihood is that some young horse, somewhere, will do something similar later this year that will be missed by those who prefer to ignore sectional times. You do not have to be in the dark when it happens.

.jpg)

Url copied to clipboard.

Url copied to clipboard.

.jpg&w=300)

.jpg&w=300)

.jpg&w=300)

.jpg&w=300)

.jpg&w=300)