The adverse weather conditions we’ve endured in Britain recently have not only had severe consequences for the National Hunt calendar – 10 fixtures over jumps have already been abandoned in 2021 – but they’ve also caused more variations in the going offered at certain all-weather tracks than might usually be the case.

The six all-weather tracks in Britain may be better-equipped to deal with the snow, frost and heavy rain that have claimed so many National Hunt cards in recent weeks, but it still requires plenty of hard work from racecourse staff to get the surface fit for racing, work that inevitably has an impact on the going compared to when the weather isn’t quite so extreme.

Specifically, the surface tends to ride much slower than usual, as evidenced by Timeform’s going descriptions for the 20 all-weather meetings that have been staged so far in Britain in 2021 (up to and including January 13). Only three fixtures have taken place on going described as ‘standard’ on the Timeform scale, leaving us with six staged on ‘standard-to-slow’ and 11 on just ‘slow’.

Old Persian's brother strikes in the snow!

— At The Races (@AtTheRaces) January 2, 2021

Bandinelli and Adam Kirby get the win at @WolvesRaces for Charlie Appleby and @godolphin... pic.twitter.com/DjfhDaR9Za

It’s worth pointing out that Timeform’s going descriptions can (and often do) differ from the official descriptions provided by racecourses. For context, there have been 142 meetings at Chelmsford since the start of 2018 where the official going description has been given as ‘standard’ but Timeform have called it slower than that. Similar disparities have also been apparent on numerous occasions at Wolverhampton (98) and Newcastle (95) during the same period.

This article written by Simon Rowlands describes in much more detail the processes that go into finalising Timeform’s going descriptions – both on turf and the all-weather – with the extract below providing a quick summary of the most important steps that need to be taken.

“Using race times to gauge the nature of the surface – something which Timeform has championed for decades – remains the best objective measure. Unlike alternatives, race times are a reflection of the surface at the times the races were run, and not at an unspecified number of hours beforehand.

“This process has improved over the years, also: not only are overall times used, but the sectional times and implied pace variations which gave rise to them are used also. A succession of slowly-run races, resulting in slow overall times and a possible assumption that the surface is more testing than is truly the case, are identified and allowed for more than might once have been the case.”

Slow times have certainly been a feature in recent races at Southwell, which is perhaps the all-weather track in Britain that faces the biggest challenges as a result of low temperatures. Southwell’s clerk of the course Paul Barker explains how they can manage up to a point before more drastic measures have to be taken to make their unique fibresand surface fit for racing.

“If the temperatures are hovering around -1C or -2C, then we tend to just salt the track, which usually involves applying 10 tonnes of salt,” Barker explains. “Obviously, we don’t just lay it on the top, we have to work it in to about 100mm. Then we just leave it and the salt would do the work for us.

“Anything lower than -2C, then we’d do the same process at the start, but we’d have to continuously work the track all night at a depth of 100mm. You’ve got to continually move the surface, because if we didn’t move it, it would freeze. Obviously, it becomes very slow once we’ve worked it to that depth because the whole surface has been loosened up. It could take anything up to a week to get it back up to standard again, depending on how much rain we get.”

The first two fixtures at Southwell in 2021 were both staged on going described by Timeform as ‘standard’, but the surface has been ‘slow’ for two of the last three meetings after temperatures dipped to a low of -4C during the second week of this year, giving the ground staff little option but to harrow the track to a much greater depth than usual.

“Normally, we’d only have to tickle the top 25mm,” Barker adds. “For a racing surface, we’d tend to just take the hoof prints out and then flat roll it, so it doesn’t get any deep work whatsoever. And, the wetter it gets, the quicker it gets because it becomes tighter.”

Huge thanks and credit to the Southwell grounds team, led by @SouthwellClerk who worked through the night last night in -4° conditions to prevent the fibre sand from freezing ❄️ pic.twitter.com/9g8OuHG52Z

— Southwell Racecourse (@Southwell_Races) January 1, 2021

Arena Racing Company (ARC), the owners of four of the six all-weather tracks in Britain, announced in December that it is planning to replace the fibresand at Southwell with the tapeta surface that has been installed at Newcastle and Wolverhampton in recent years. Barker has already canvassed the opinions of his colleagues to find out how tapeta is affected by the sort of low temperatures that we’ve endured recently, including Wolverhampton’s clerk of the course Fergus Cameron.

“All of the surfaces will react differently,” Cameron says, “but in terms of tapeta, the material itself won’t freeze and the binder is water repellent. The only thing we will do if we have frost is we’ll actually open the track up. The moment you open it up, any moisture in there will be repelled and it then goes down through the track.

“On the day, we’ll set it back down again to racing speed. The binder gets more effective the colder the material gets, so if we have a frost overnight, one thing we wouldn’t have a problem with is being able to set the track back to standard again. There’s not really any danger of it riding slow on a raceday if it’s cold.”

Cameron acknowledges that race times recorded for recent meetings at Wolverhampton have frequently been slower than standard, but he reports that this is mainly a result of the volume of racing the track has had to contend with recently rather than the cold weather, with the busy spell not giving them as much time as usual to prepare a ‘standard’ surface.

“When we have a lot of racing very close together – we had five days racing in six days last week – what we don’t want to do is to completely throw the form guide out by digging the track down deep on the morning of racing when we haven’t really got time to get it back again,” Cameron explains.

“We work the surface fairly deep on a regular basis. Today we worked the track down to six inches and we’ll then leave that to settle for Monday’s race meeting. By the time we get to Monday, it will be back to standard. That ensures the track is not too compact and too tight for the horses running on it. It’s primarily all around safely for us, but obviously consistency for the form guide is also essential, otherwise it devalues the product.”

A busy day for the estates team @WolvesRaces but all for a good cause. pic.twitter.com/Bi3GCqB788

— Fergus Cameron (@FergusCameron6) December 29, 2020

So, what else can we learn about the various all-weather tracks in Britain and the way that they ride when the surface is described as ‘slow’? It’s worth revisiting the article I wrote back in May looking at whether front-runners have any more or less success at Southwell than you might typically expect given their overall strike rate.

For context, you’d be operating at a strike rate of 15.7% if you backed every horse who recorded an Early Position Figure (EPF) of 1 in Flat handicaps in Britain since the start of 2016. By way of comparison, front-runners have a strike rate of 18.2% in Flat handicaps at Southwell during the same period.

Front-runners also have an above-average strike rate in Flat handicaps at Chelmsford (17.2%), but there is a drop-off in the performance of front-runners at the other all-weather tracks in Britain, namely Kempton (15.1%), Lingfield (14.8%), Wolverhampton (11.3%) and Newcastle (11%).

We can also compare how runners who recorded an EPF of 1 performed at each of those tracks when Timeform’s going description was given as ‘standard’ and when it was labelled ‘slow’. For example, front-runners in Flat handicaps at Lingfield have a strike rate of 14.4% when Timeform have called the surface ‘standard’, but there is a significant dip to just 8.5% when it was ‘slow’.

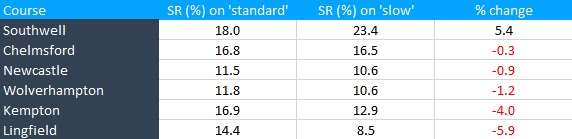

Strike rate of front-runners on ‘standard’ going vs ‘slow’ going at all-weather racecourses in Britain (Flat handicaps since the start of 2016)

Aside from the drop-off in performance of front-runners at Lingfield when the surface is riding slower than usual, the main point of interest from this data is how front-runners do even better on ‘slow’ going at Southwell than they do when it is called ‘standard’.

The cause of this increase is open to date, but perhaps the most significant factor is how much more kickback the fibresand surface produces compared to the polytack/tapeta installed at the other all-weather tracks in Britain. Some horses simply won’t face up to it, and it’s no coincidence that those who do often go on to have long and successful careers at Southwell, with the surface very much lending itself to the course specialist (think La Estrella or Stand Guard).

Front-runners obviously have the advantage of being kept away from the kickback produced by other runners, and it stands to reason that the deeper and slower the surface gets – or “loosened up” as Paul Barker described it – the more kickback there is going to be, causing even more problems for runners trying to deliver a challenge from off the pace.

Incidentally, it’s worth pointing out than when Southwell recently held meetings on consecutive days on January 8/9, eight of the 14 races were won by horses who recorded an EPF of 1. The going was described by Timeform as ‘slow’ on the first day – when five of the seven winners made all – and ‘standard-to-slow’ on the second day.

These trends may not last much longer if ARC proceed with plans to replace the fibresand at Southwell with tapeta, but there are still some interesting angles to be considered at the track until then, with the impressive record of front-runners when the going is ‘slow’ perhaps chief amongst them.

.jpg)

Url copied to clipboard.

Url copied to clipboard.

.jpg&w=300)

.jpg&w=300)

.jpg&w=300)

.jpg&w=300)

.jpg&w=300)