They say you should never meet your heroes, and “they” have a habit of being right. Such avoidance is easier to achieve if, like me, you have few heroes in the first place. All the same, I managed not only to meet one of them but to work for them. On a sample of one, “they” might have got this saying wrong at least.

June 11, 2014, marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the death of Phil Bull, founder of Timeform, polymath, innovator, mathematician and iconoclast. It should be added, for the sake of balance, that Bull was also renowned for being, at times, irascible, cantankerous and earnest almost to a fault.

Bull was 79 when he died, and his day-to-day involvement in the running of Timeform was small by the time I turned up there, fresh-faced and wet behind the ears, in 1986. It would be an exaggeration to say that we had much to do with each other in the near-three years during which we overlapped, but there were occasions.

Such as the time I was invited to his private box during racing at Haydock to find myself in the company of just Bull and Alex Bird, both legendary punters. Bull and Bird dug out the same good bet in the big race and proceeded to invest sizeable four-figure sums, before Bull turned to me and asked “do you want anything on as well, young man?” On a pittance at the time, I plucked up the guts to say “£20, Mr Bull”, which was met by stunned silence. The horse got beat.

Bull, famously, though possibly apocryphally, once countered a complaint at a Timeform interview about the derisory starting wage on offer by saying “if you can’t make twice that sum a year from betting, you shouldn’t be coming to work here in the first place”. I’m guessing that was met by stunned silence, too.

There was also the time when I was drawn against Bull in the Timeform snooker tournament, held at his mansion on the outskirts of Halifax. Bull had been no mean player in his time, and had counted snooker legend Joe Davis among his close friends, but was not only old by then but had always been of small stature.

I adopted a policy of leaving the cue ball in the centre of the table, where he could barely reach it, even with a rest and extension, and we might still be there now – caught between my stubborn incompetence and his resolute frailty – had he not bluntly observed that there was a bottle or two of his vintage wine waiting if we got this over and done with some time that century.

Bull had been a major force in British racing earlier in that century, as an owner, as a breeder, as a punter (he made the equivalent of about £8m in today’s terms) and as a reformer. His activities earned him tenth place in the “Makers of 20th Century Racing” in Randall and Morris’ “A Century of Champions” and the remarks:

“[Bull] did more to change the character and conduct of British racing than anyone else in modern times....A punters’ champion and outspoken critic of the racing establishment, he campaigned for many reforms and innovations which were usually not adopted until many years later.....in terms of intellect, logic and vision, he dwarfed every other man of his time in [the] sport....”

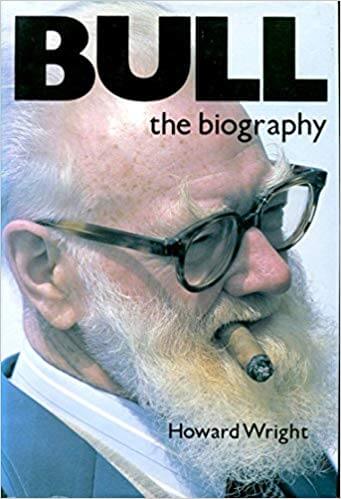

If you want a fuller idea of what Bull was like, then Howard Wright’s candid and excellent “Bull: The Biography”, published by Timeform, is a must-read.

It may seem fruitless to speculate as to what Bull would have made of 21st century racing and life, but it can be fun.

It is a fair bet he would have loved betting exchanges and the emergence of big data. Never one to suffer fools under any terms, let alone gladly, it seems a pound to a penny that he would long since have been banned from the Betfair chatroom and blocked, or been blocked by, the vast majority of Twitter (though a parody account – @BullyTF – has got into a disappointingly small number of scrapes so far).

And it seems 1.01 that Bull – who was looking into things like sectional timing shortly before his death – would have been as exasperated now by the glacial rate of change and by pig-ignorant officialdom as he was then. I doubt he would have rated Britain’s Got Talent all that highly, either.

Bull’s was a life well-lived, much of it serious but some of it playful and light-hearted. Perhaps his greatest legacy was to inspire subsequent generations of racing analysts to adopt healthy scepticism and to make a career of following what he once memorably described as “The Great Triviality”.

Twenty-five years on, racing is a poorer place for his absence.

.jpg)

Url copied to clipboard.

Url copied to clipboard.

.jpg&w=300)

.jpg&w=300)

.jpg&w=300)